The wool industry has berated itself over time for still using the open cry auction method to sell wool (discover price) and allow greasy blending of farm lots into mill consignments (something not usually mentioned). Wool is sold in farm lots, and it is the number of lots which can be sold in a given time which is a key constraint on the efficiency of wool selling. Here is a simple way to improve the efficiency of wool sales.

During the past 12 months some 1.6 million farm bales of wool were sold at auction in 289,000 lots, averaging 5.5 farm bales per lot. There is always discussion, especially among logistics providers, about the optimum size of farm lots or really the non-optimum which means what is too large and what is too small. The answer to this is not straight forward as it involves the physical size of mill consignments, the use of containers to ship wool and the wool characteristics of each farm lot. A large lot will be harder to fit into a consignment (meeting the required wool specifications) and into the required number of containers (roughly units of 100 bales). The task is even more difficult if the wool specifications of the lots are not “bread and butter”, say for example the wool has a high vegetable fault or very low staple strength. Large lots can sell for full value, but it is harder for the exporters to fit them in.

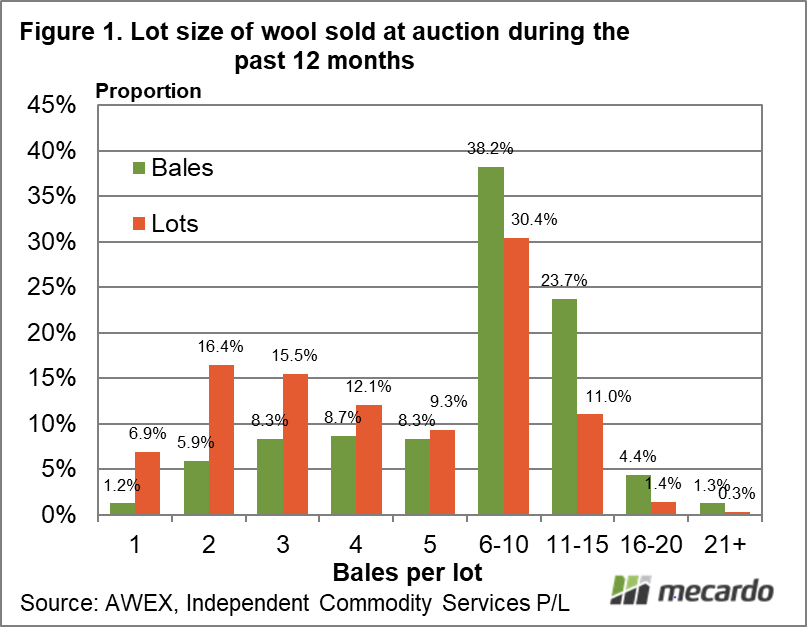

What about the other extreme, small lots? In this case small lots are considered as one and two bale lots. There are plenty of them. Figure 1 shows the distribution of wool sold in the past 12 months by lot size. The proportion of farm bales and number of lots is given for each lot size. Single bale lots accounted for 1.2% of farm bales sold in the past year, while accounting for 6.9% of lots. Two bale lots accounted for 5.9% of farm bales sold and 16.4% of lots. Together one and two bales lots in the past year accounted for 7.1% of farm bales sold and 23.3% of lots, effectively a quarter of lots sold at auction.

Here is a way to make auction sales more efficient, reduce the number of one and two bale lots sold. How? There is a good chance that better packaging of wool on farm could go a long way to reducing the number of small lots, although not necessarily all as there will be some circumstances where they are warranted.

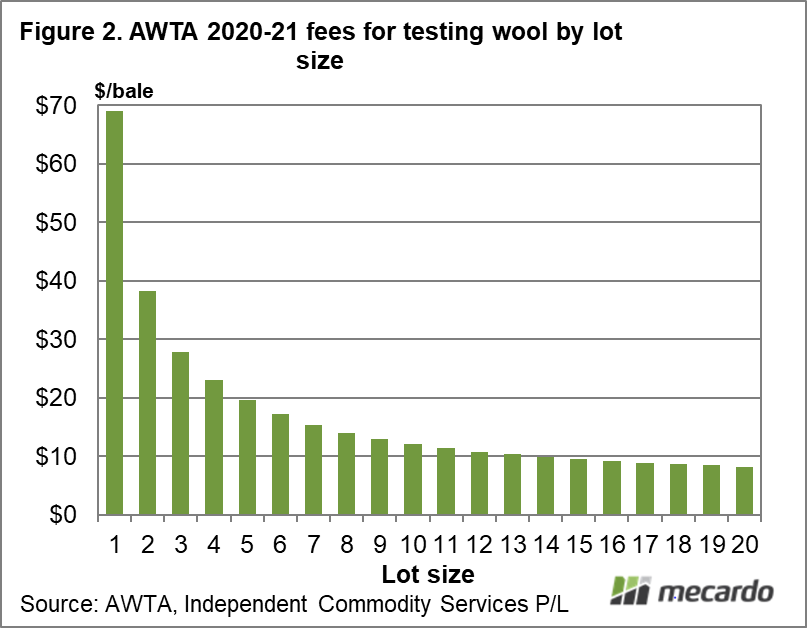

Figure 2 shows the calculated costs of AWTA testing for last season (2020-21) by lot size, (view current AWTA fees here). The schematic assumes the wool is tested for staple measurement (length and strength) in addition to the basic micron, yield and vegetable matter. It shows there is a clear penalty in the per bale cost for testing single bales. Out of interest for the current season to date, some 10% of single bale farm lots were non-merino, selling on average for $850 per bale so the cost of testing per bale is substantial for these lots.

In the late 1980s George Shenton, of the Wool Agency in Western Australia, gave a series of talks in the eastern states about the careful on farm packaging of wool for sale. The points he made then about such careful packaging, in the main, still stand. Minimising small lots is part of carefully packaging wool for sale.

What does it mean?

Small lots are expensive to sell, so there is a financial incentive to package wool on farm aiming to limit the number of small lots. In addition the sale system (auction or electronic) would benefit from a reduced number of small lots, as they are more costly to buy.

Have any questions or comments?

Key Points

- One and two bale farm lots account for 7.1% of farm bales sold but account for nearly one quarter of lots sold at auction.

- The number of lots is a key limiting factor for auction sales, something which a reduced number of small lots would help greatly.

Click on figure to expand

Click on figure to expand

Data sources: AWEX, AWTA, ICS, Mecardo