There is nothing like war to create rampant volatility in commodity markets. When the war is between major grain and oilseed exporters it takes price swings to another level. Last Friday’s article outlined the backwardation in the market, but the volatility still offers opportunity.

US grain producers with stock on hand have been the main beneficiaries of the conflict driven price rises of recent weeks. The CME March Soft Red Wheat (SRW) hit 1348¢/bu on Friday, which at current exchange rates equates to $669/t. In 10 days the spot market has ralled 66%.

With the March SRW contract about to go into delivery there is likely some sort of squeeze involved here, with the May contract well behind, at 1209¢/bu. Still, May is priced at $611/t in our terms, which is a record price, historically, if you can get wheat to the US by then.

Locally spot prices have rallied, but to a lesser extent. ASX May 22 futures traded at $422/t on Friday, which is a massive discount, but likely reflective of shipping timeframes to reach markets.

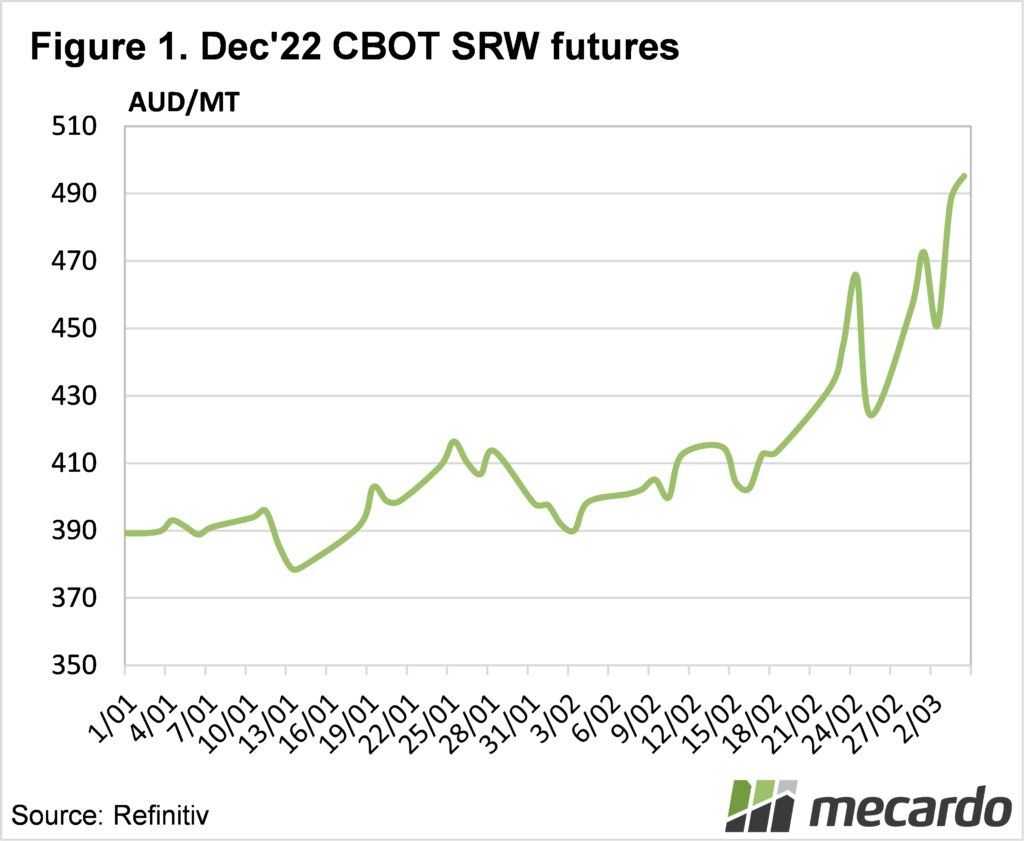

For grain growers there are opportunities in deferred markets, with Dec-22 SRW Futures rallying above $450/t, in response to high spot markets. Figure 1 shows how Dec-22 has swung in the last fortnight, peaking at $495/t on Friday. Locally Jan-23 ASX Wheat Futures are around $400/t which is a heavy discount under normal circumstances. We all know these are not normal circumstances.

When there is such uncertainty and volatility in markets the usual intuitive strategy is to sit out, and ‘see what happens’. History tells us that times of extreme volatility are the best times to sell.

Those with the biggest appetite for risk would sell the May or July SRW Futures as they have the furthest to fall. The risk lies in the fact that local prices aren’t tied all that closely to SRW at the moment.

A more consertivative strategey is to sell Dec 22 SRW futures or swaps at close to $500, in the expectation that the ‘basis’ or price difference between SRW and local wheat prices closes up, resulting in a new crop wheat price close to $500/t. This would happen either through local markets rising to meet SRW, or SRW falling and providing a profit.

Forward contracts for new crop, or ASX Wheat futures are the least risky option, and will simply lock in a price around $400/t, but it leaves $100 of basis on the table.

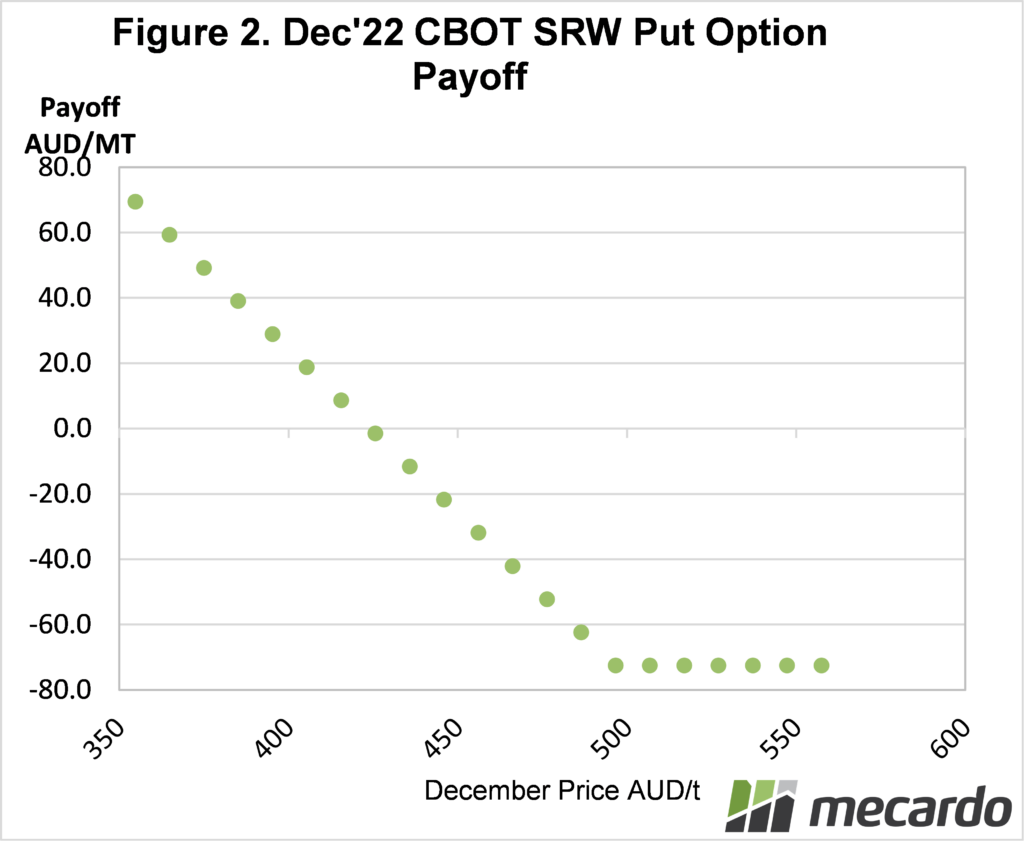

The least risky strategy is to spend some money on SRW Put options. A Put option is like price insurance, where a premium is paid to guarantee a minimum price.

Figure 2 shows the payoff at different December price levels for a Put option bought at a strike of 980¢/bu for a premium of 143¢. In our terms you pay $72/t to guarantee a minimum price of $496/t. Once the price falls below $496 the option starts to payoff, but only offers a profit once the price hits $425/t. If the market is higher than $496 the premium is lost, but the theory goes that you participate in all the upside when selling physical wheat.

What does it mean?

There are a multitude of hedging strategies, and they all have pros and cons, but as always, the higher the risk, the higher the potential reward. Options always look expensive, but when volatility is so high, they become even more so. Still, locking in a SRW floor price above $400 would, under normal circumstances, be very attractive, but you can’t account for some geopolitical factors.

Have any questions or comments?

Key Points

- Extreme wheat prices are being driven by the Black Sea conflict.

- Forward markets are at a discount, but remain at extremely strong levels.

- There are a number of hedging strategies, but there remains risk and reward in all of them.

Click on figure to expand

Click on figure to expand

Data sources: CME, ASX, Mecardo