Lamb and mutton prices have spent almost all of 2022 either in decline, or way lower than in 2021. The first half was relatively steady, but volatility crept in after July, and we are still seeing wild swings in the market. Here we take a look at how 2023 might play out.

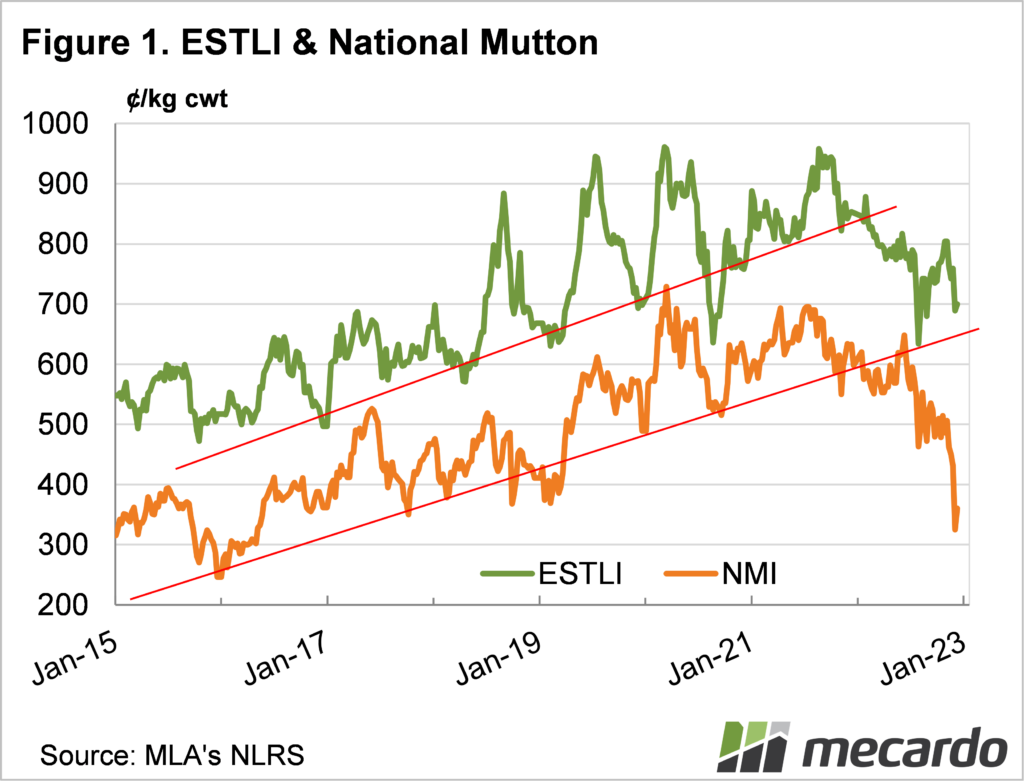

The long-term sheepmeat upward trend has been well and truly broken. Figure 1 shows that the price rise that has been in place since 2013 was breached back in February, and unlike the Covid declines in 2021, the market hasn’t bounced back.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise to see lower sheepmeat values. The tight supply and increasing demand cycle that existed for 7 years has turned. The flock rebuild that has been in place since 2019 has finally resulted in ample lamb supplies, and sheep numbers are also increasing.

On the demand side rising processor costs, labour shortages, and now global economic doldrums have all conspired to see processors receive less for lamb and mutton. There was only one-way prices could go.

So what’s in store for 2023? If we go back to the last time a rising trend was broken, and add in a bit of knowledge of commodity price cycles we can get an idea.

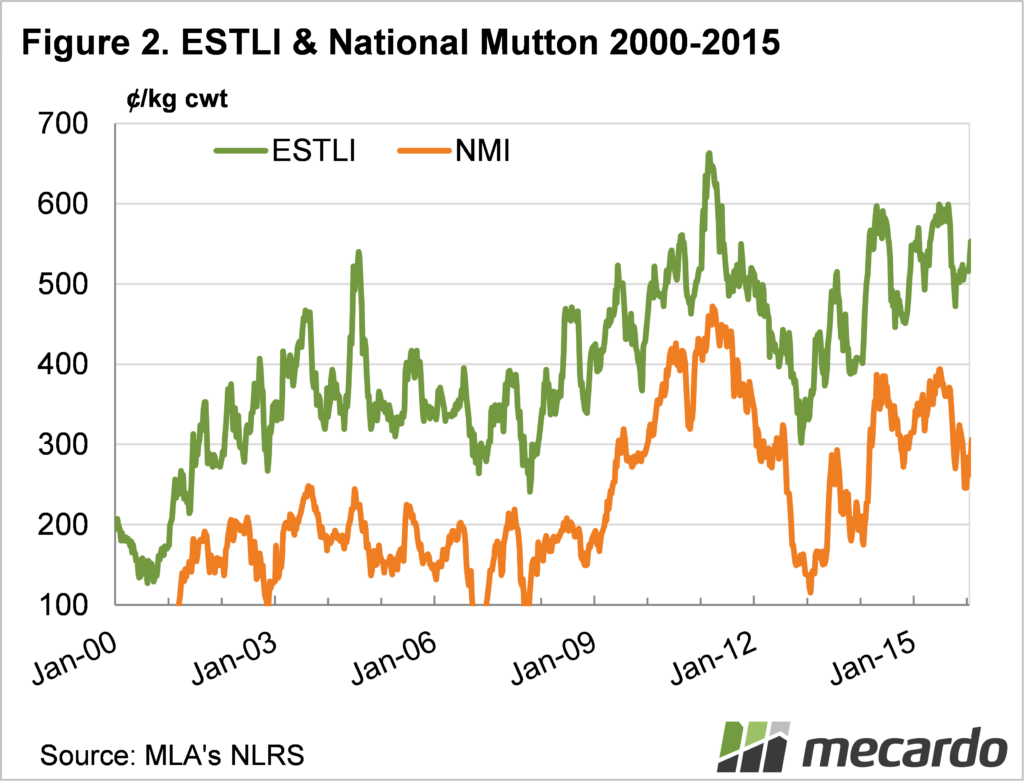

Figure 2 shows the rise and fall of lamb and mutton prices from 2009-2011, and the subsequent decline. The rising cycle was much shorter then, but we can still take some lessons. After the price peak, both the Eastern States Trade Lamb Indicator (ESTLI) and National Mutton Indicator (NMI) returned to the previous five-year average, bottoming out 18 months from the peak.

From the bottom, prices improved returning to around the average of the stronger 2010-2011 prices within 18 months of the low. The 18-month time period fits nicely with the production cycle. Falling prices saw growers adjust their flock intentions, selling more sheep and exacerbating falls. The following year supply steadied and prices returned to a more profitable level.

Commodity price cycles tend to move in similar ways. After things have got very expensive, supply and demand adjust, seeing prices fall. The previous average is then seen as ‘cheap’ and demand improves. Similarly, producers will pull back supply at previous averages, as costs have gone up and the marginal return needs to be higher to make a profit, hence the old average becomes the new low.

What does it mean?

Applying this theory to the current markets is a very rough and ready way to forecast but useful nonetheless. The five-year average ESTLI from 2016 to 2020 was 680¢/kg cwt. The NMI was 480¢/kg cwt. Prices have reached these levels, or in the case of the NMI overshot by a long way.

The coming years should be a year of consolidation. The extreme highs of 2020-21 are behind us for a while, but we are likely to be close to lows now. Prices are likely to bounce between current levels and the prices seen earlier in the year for much of 2023.

Have any questions or comments?

Key Points

- The rising trend of lamb and mutton prices has been well and truly broken in 2022.

- Historically previous averages represented new lows for livestock values.

- In 2023 prices should consolidate between current values and earlier 2022 prices.

Click on figure to expand

Data sources: MLA