There is the well noted ‘fight for acres’ between sheep and cropping, especially in the sheep/wheat zones of the country. Cropping has been winning for decades, with the sheep flock on the decline. There is a smaller battle, however, between Merinos and meat sheep. We received a query recently as to whether the wool price crash is going to see a lift in slaughter lambs.

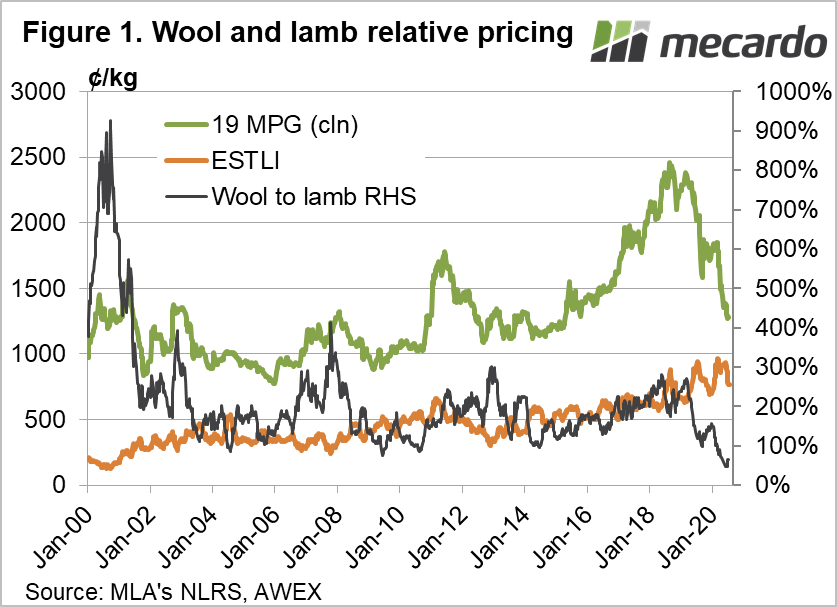

Back in April we took a look at the falling wool market and relatively strong lamb market and surmised we might see further declines in the wether flock. Even with the recent fall in lamb prices, the relative price of wool has hit new lows (Figure 1).

Low wool prices have historically led to increases in cropping area, but the drought and subsequent destocking have left plenty of room for more sheep now. The question we had is how falling wool prices are going to play out in the mix of Merinos and meat sheep going forward.

The theory is that low wool prices, both in absolute terms, and relative to lamb and mutton, will lead to more Merinos being joined to terminals, and meat maternal flocks being bred up to replace Merino flocks.

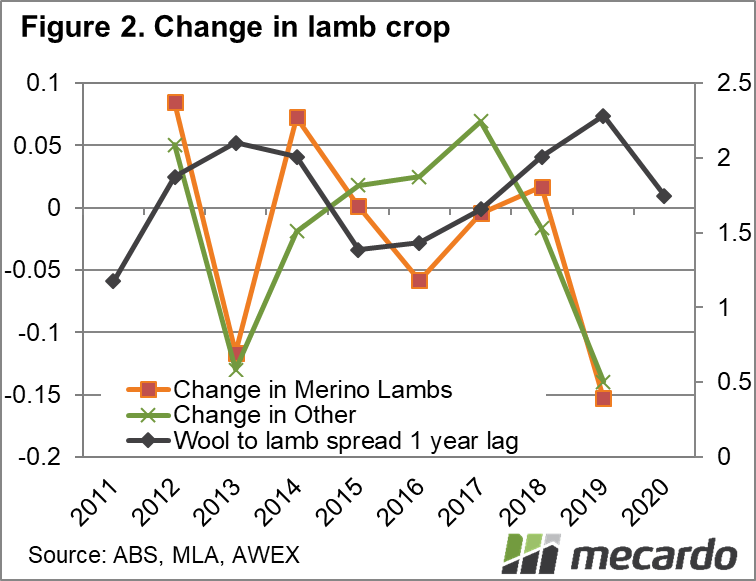

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Agricultural survey gives us the best data for looking at what type of sheep are being joined, and lambs being produced. Simply looking at the lamb crop doesn’t give a clear picture, as it fluctuates wildly with seasons, and this impacts both Merino and meat sheep. We can, however, look at changes in types of lambs marked, and how this relates to the wool/lamb spread.

Figure 2 is a little complicated, but it does show up a trend towards more ‘other’ lambs when the wool price is low relative to lambs. Figure 2 shows the year on year change in lambs produced and the average 19 micron wool premium over the Eastern States Trade Lamb Indicator (ESTLI) for the previous year.

We can see that in 2014 there were more Merino lambs produced in response to two years of strong wool premiums. Subsequently, from 2015-2017 more ‘other’ lambs were marked, while Merino lambs were steady or lower. Rising wool premiums saw this reverse in 2018 before drought smashed all lamb production in 2019.

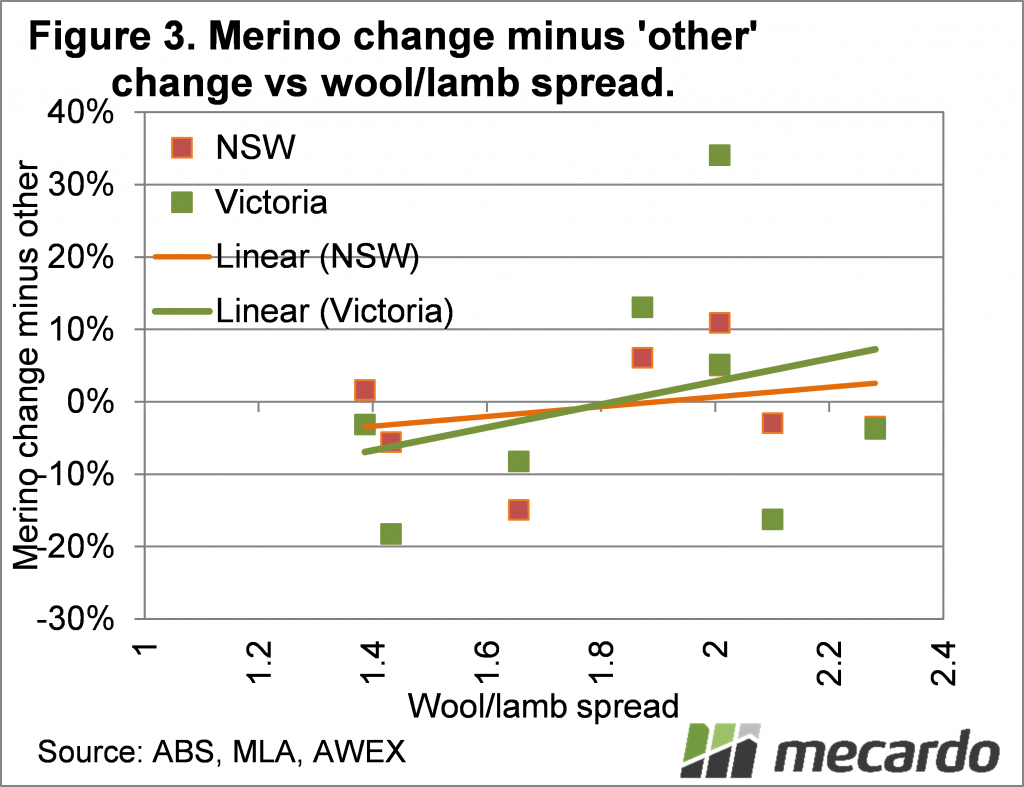

The reaction is not the same for all areas. Again, it’s complicated, but figure 3 shows the change in Merino lamb production, minus other lamb production, versus the wool/lamb spread for NSW and Victoria. It’s a small sample, but we can see the wool/lamb spread has more impact on the change in lambs produced in Victoria and less impact in NSW.

What does it mean?

When setting out on this analysis we thought there would be more of a lag between the wool/lamb spread, and changes in lamb production. It does seem however, there is some impact on joining decisions the year following changes in the wool/lamb spread, especially in Victoria.

Figure 2 shows that the 2019-20 wool/lamb spread hadn’t fallen too far, and as such there shouldn’t be a large change in relative lamb production. However, if the wool lamb spread stays under 100%, as it finished the first half of 2020, we can expect a swing towards meat lambs next year. The impacts on price will begin to be felt in spring 2021.

Have any questions or comments?

Key Points

- Wool prices are very weak relative to lamb prices, even after recent falls in lamb values.

- Over the last 10 years, weaker relative wool prices have led to proportionally more meat lambs being marked.

- If wool prices remain weak, there will be more ‘other’ lambs marked next year, relative to Merinos, with impacts on price.

Click on graph to expand

Click on graph to expand

Click on graph to expand

Data sources: MLA, NLRS, AWEX, ABS, Mecardo