Rising fertilizer costs are the talk of farming industries at the moment. Higher fertiliser costs will impact all sectors of agricultural markets, with croppers likely to see the strongest impacts, but pasture-based systems will also have some tough decisions to make.

Fertiliser is one of the main inputs in Australian agricultural businesses. For grain cockies the relationships between soil fertility and production are well understood, which is why when nitrogen is cheap, plenty of fertiliser is used. Those relationships are no doubt going to be analysed a lot more, along with existing soil fertility, as the rising price of nitrogen will drive efficiency.

Canola is the highest nitrogen user of dryland crops. The Grain Research and Development Council put the average nitrogen removal of canola crops at 40kgs/t of grain produced. A further 10 kg/t is contained in the stubble.

We’ve had some queries as to the impacts of rising fertiliser costs on cropping margins. There is no definitive answer obviously, as every farm, indeed, every paddock is different, but we can look at some average costs of nitrogen removed, and compare it to the value of canola produced.

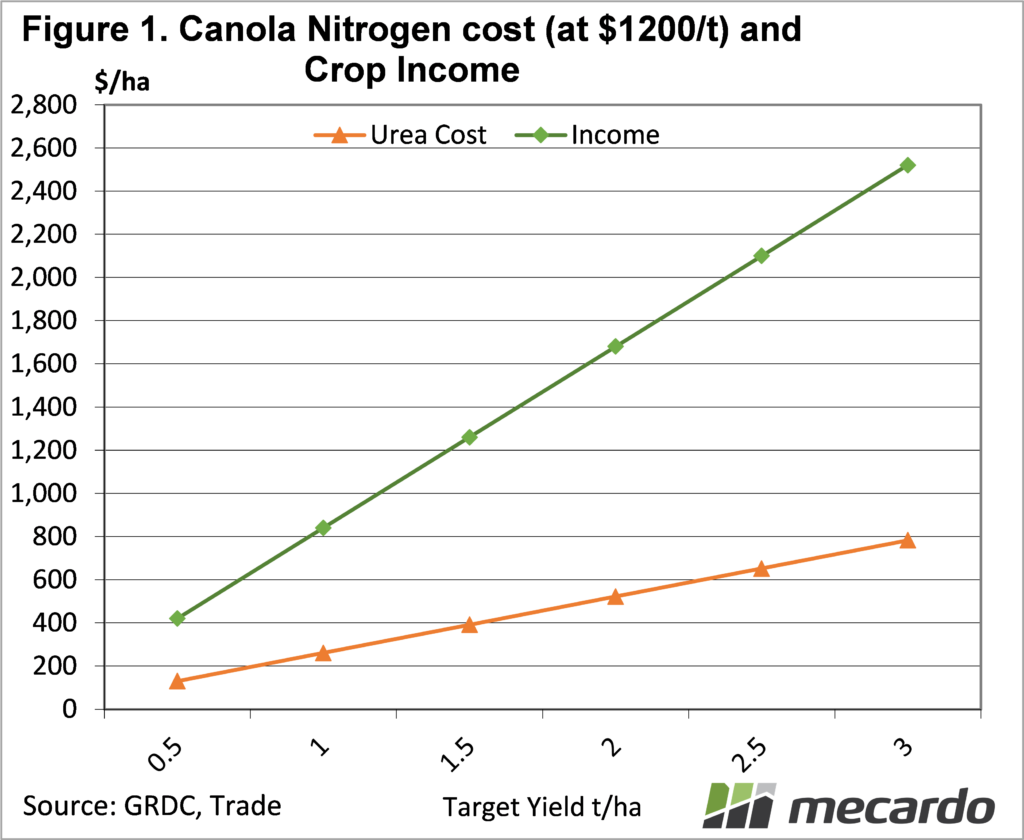

Figure 1 shows the cost of nitrogen used per hectare, versus the value of the canola crop per hectare at different target yields. The chart assumes urea costs $1200/t and doesn’t include spreading, while the canola price is estimated at $850/t. The chart assumes all the nitrogen required (40kg/t produced) is spread as urea, which obviously isn’t the case. Nitrogen already present in the soil will be used, as will that in sowing fertilizer, although that is just as expensive.

We can see in figure 1 that spreading urea to increase crop yields still makes sense for higher rainfall areas, where response is more reliable. It does increase risk for the canola producer though. Where urea cost $400/t in the not too distant past, the cost of putting a 2t crops entire requirement out was $173/t, it is now $521/t.

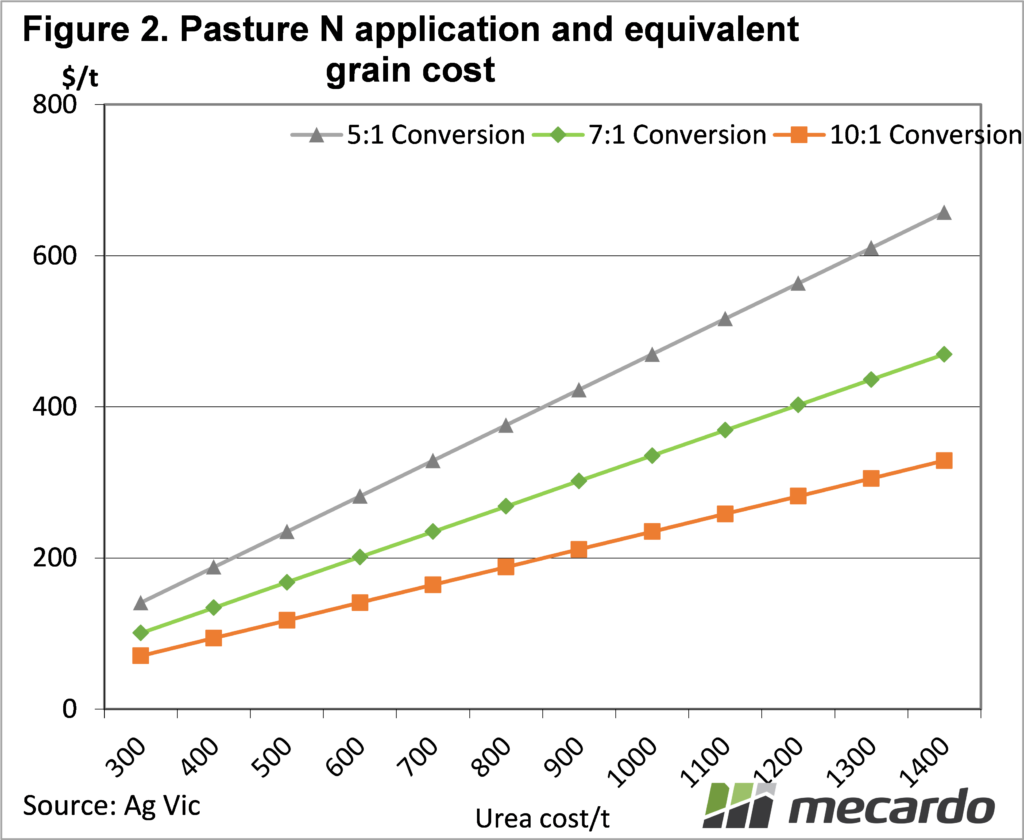

In pasture situations, the cost of nitrogen is sometimes worked back to the value of extra feed produced, and the equivalent cost of buying in feed. Figure 2 shows the equivalent grain cost at different conversion rates, based on the price of urea. The 5:1 conversion is what might be expected in winter, while 10:1 is in a good spring.

At $1200/t urea application at 5:1 conversion makes grain cheaper at anything under $563/t. It makes more sense in terms of boosting good quality hay or silage in the spring, with the equivalent feed cost of grain at $281/t.

What does it mean?

While rising fertilizer costs won’t drive many farmers out of business with current very strong commodity prices, it will drive efficiency, and make growers think twice before throwing it out. For grain it might make marginal production areas less appealing, with the sunk costs, and therefore risk, increasing.

No doubt some thought will go into crop rotations which increase soil nitrogen, which might decrease the amount of country planted to the main crops next year.

For livestock and dairy producers, it might mean feeding more grain and hay, and using less urea in the winter to boost pasture growth, as the cost of the extra feed is now getting prohibitive.

Have any questions or comments?

Key Points

- Rising fertilizer costs will drive growers to be more selective about application.

- For marginal cropping areas increased fertilizer costs will increase risks markedly.

- In pasture systems, supplementary feed could be cheaper than urea in the winter.

Click to expand

Click to expand

Data sources: GRDC, AgVic, Mecardo